Broken Balance: The U.S. Economic Journey

In 2025, the U.S. faces intertwined crises—manufacturing decline, fiscal deficits, and trade imbalances—rooted in decades of policy shifts, global dynamics, and the unraveling of its post-war economic model.

In 2025, the United States stands at a historic economic crossroads, grappling with three interlinked crises: a hollowed-out manufacturing base, an unsustainable fiscal deficit, and a persistent trade imbalance. These crises are not sudden—they are the cumulative result of decades of policy decisions, structural transformations, and global realignments. To understand how the U.S. arrived here, one must trace the evolution of its economic paradigm—from post-war dominance and the Bretton Woods system to financialization, globalization, and recent populist pushback.

Bretton Woods and the Dollar's Rise (1944–1971)

In the aftermath of World War II, the United States emerged as the world's unchallenged economic powerhouse. At Bretton Woods in 1944, it used that position to shape a new global financial system. The U.S. dollar was pegged to gold, and all other currencies were pegged to the dollar. This anchored the world economy—and cemented the dollar’s centrality.

But this system had a flaw. It relied on the U.S. maintaining gold reserves to back dollars in circulation. As America began running trade deficits in the 1960s and spending escalated due to the Vietnam War and Great Society programs, confidence in dollar convertibility waned.

The Nixon Shock – End of the Gold Standard (1971)

In August 1971, President Richard Nixon unilaterally suspended dollar convertibility into gold, effectively ending the Bretton Woods system. This “Nixon Shock” marked the birth of the fiat dollar system. The dollar was no longer backed by gold, but by the promise of the U.S. government. Currencies began to float freely.

This unleashed decades of financial innovation, credit expansion, and global capital flows—but it also planted the seeds of future imbalance. The dollar’s dominance allowed the U.S. to live beyond its means, running persistent trade deficits while exporting inflation to the world.

The Petrodollar System – A Strategic Pivot (1970s–1990s)

To stabilize dollar demand, the U.S. struck a crucial deal with Saudi Arabia in the 1970s: oil would be priced in dollars. This created the “petrodollar” system, reinforcing global dollar demand and giving the U.S. extraordinary leverage. In return, oil producers recycled their surpluses into U.S. assets, especially Treasury bonds.

This petrodollar arrangement became the linchpin of U.S. hegemony, enabling the country to finance its deficits cheaply. But it also deepened America’s dependence on foreign financing—and made its economy vulnerable to oil shocks, Middle Eastern politics, and speculative capital flows.

The Plaza Accord (1985): Coordinated Currency Realignment

In response to a ballooning trade deficit and an overly strong dollar, the U.S. and its G-5 partners (France, West Germany, Japan, the U.K.) signed the Plaza Accord in 1985. The agreement aimed to depreciate the dollar through coordinated currency intervention.

- The dollar fell approximately 25% over the next two years.

- U.S. exports became more competitive, partially easing trade imbalances.

- However, Japan's sharply appreciating yen contributed to asset bubbles and eventually Japan's "Lost Decade."

While the Plaza Accord marked a rare moment of global monetary cooperation, it also highlighted the risks of currency manipulation. Its effects were temporary, and deeper structural trade issues persisted.

Globalization and China’s Rise (1980s–2000s)

China’s emergence as the “world’s factory” was one of the most profound global shifts. Beginning with Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms in 1978, China transitioned from an agrarian society to a manufacturing powerhouse. Through Special Economic Zones (SEZs), infrastructure investment, low labor costs, and business-friendly policies, China attracted waves of foreign investment.

China’s 2001 entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) triggered a massive wave of offshoring by Western firms. U.S. companies moved production to China, slashing costs and increasing profits. American consumers benefited from cheaper goods—but at the cost of millions of manufacturing jobs and an erosion of the industrial base, particularly in the Midwest.

Meanwhile, China used its trade surplus to amass trillions in dollar reserves, becoming a top holder of U.S. debt—and a strategic rival.

The Great Financial Crisis (2008): A Fault Line Exposed

The 2008 financial meltdown was the biggest economic crisis since the Great Depression. It exposed the fragility of a financial system built on leverage and speculation. Wall Street institutions collapsed. Millions lost homes and jobs. The Fed responded with ultra-low interest rates and quantitative easing (QE).

Though recovery followed, the post-crisis economy was uneven. Asset prices soared, but wages stagnated. Inequality widened. And the precedent of cheap credit became hard to reverse.

The First Trade War: U.S.–China Economic Confrontation (2018–2020)

By the late 2010s, discontent with globalization and growing concern over China’s trade practices triggered a dramatic shift in U.S. economic policy. Under President Donald Trump, the U.S. launched its first modern trade war against China in 2018—marking a significant departure from decades of free trade orthodoxy.

Trump’s administration accused China of unfair trade practices, including intellectual property theft, forced technology transfers, state subsidies, and currency manipulation.

A partial truce was reached, with China agreeing to increase purchases of U.S. goods by $200 billion. Many tariffs remained in place.

While it failed to shrink the overall trade deficit, the war marked a turning point toward decoupling and strategic industrial policy.

COVID-19: A Global Reset (2020–2022)

The pandemic upended everything. Lockdowns shattered supply chains. Governments unleashed massive fiscal stimulus. The U.S. alone spent trillions, pushing national debt to historic highs.

While stimulus cushioned the immediate blow, it also turbocharged inflation. Supply shortages, labor disruptions, and surging demand sent prices soaring. The Fed began aggressive rate hikes in 2022 to rein in inflation, triggering volatility across global markets.

Russia-Ukraine War: Energy & Geopolitical Shockwaves

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 added new complications. Energy prices spiked. Global trade fragmented. Sanctions and countermeasures accelerated a shift toward economic blocs. Nations began seeking alternatives to the dollar and diversifying supply chains away from geopolitical flashpoints.

The Military-Dollar Nexus: Power Projection and Currency Privilege

Since WWII, U.S. military dominance has helped maintain dollar supremacy. This military-financial synergy gives global investors confidence, reinforces control over trade routes, and deters rivals from challenging the dollar.

But this model faces risks:

- Sanctions and interventions have fueled backlash and accelerated de-dollarization.

- Defense spending is debt-financed, undermining fiscal sustainability.

- Allies are drifting, as seen in Europe's push for euro-based bond markets and strategic autonomy.

The Dollar Game: America’s High-Stakes Economic Gamble

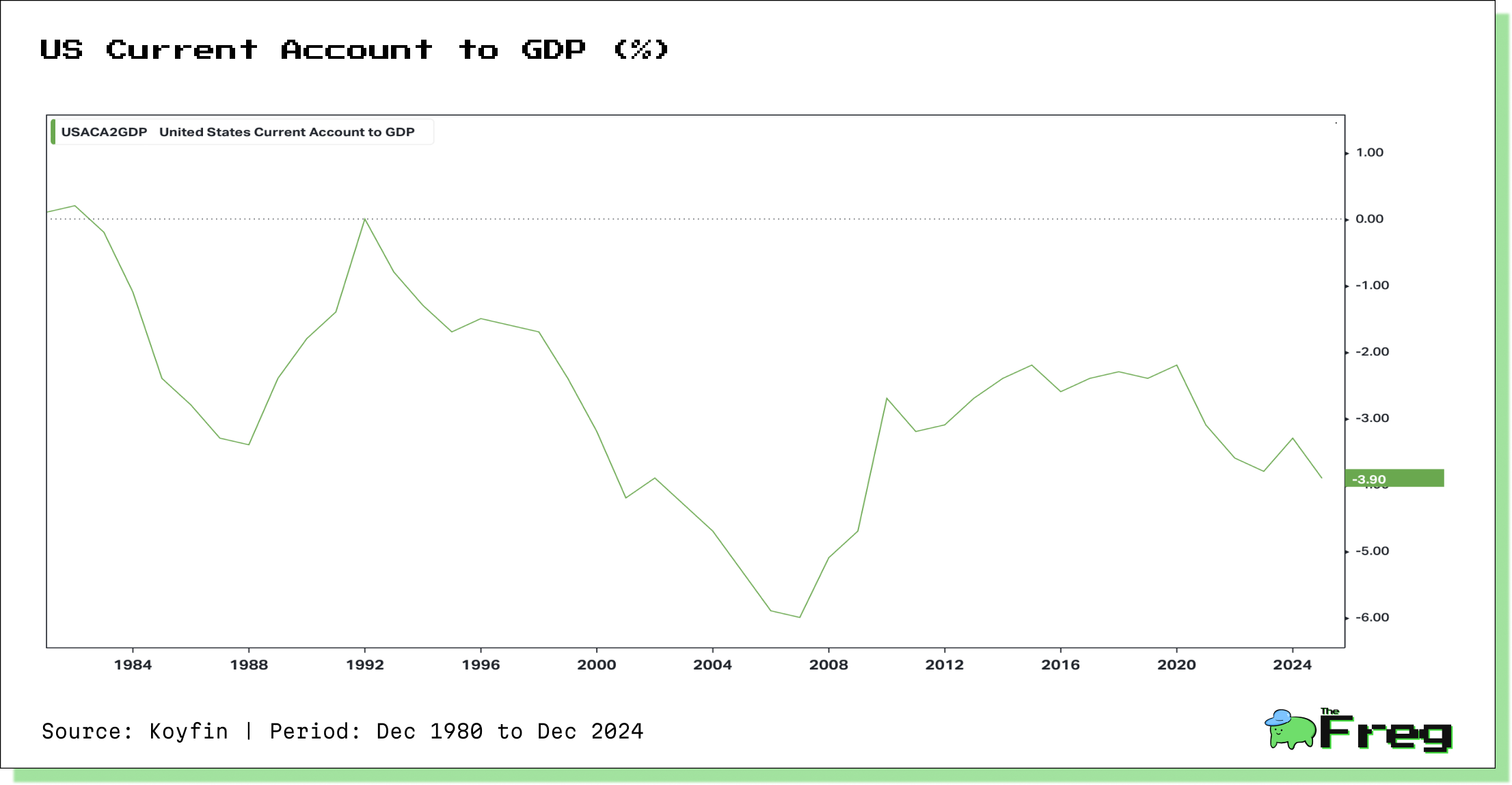

Since the early 1980s, the United States has operated under a distinct macroeconomic paradigm—one that leverages its unique position as the issuer of the world’s reserve currency. The system is underpinned by a recurring pattern: expand the money supply, run persistent trade deficits, and rely on foreign demand for U.S. assets—particularly Treasury securities—to finance both domestic consumption and government spending.

However, this model is beginning to show signs of strain. Several geopolitical and economic shifts are eroding the foundations of dollar hegemony:

- De-dollarization initiatives: Countries such as China, Russia, India, and Saudi Arabia are increasingly conducting trade in alternative currencies, including the yuan, euro, and gold-backed settlement mechanisms. The BRICS coalition, in particular, has been vocal about creating a non-dollar reserve system.

- Geopolitical realignment: U.S. sanctions and financial restrictions, while powerful, have incentivized rival nations to develop independent financial infrastructure. This includes cross-border payment systems that bypass SWIFT and reduce reliance on U.S. intermediaries.

- Domestic vulnerabilities: The combination of rising interest costs, deteriorating fiscal discipline, and an overreliance on foreign creditors introduces significant risks to debt sustainability. If demand for U.S. debt weakens, the U.S. may be forced to offer higher yields to attract investors, thereby raising borrowing costs across the economy

Despite growing calls for de-dollarization, the U.S. dollar remains entrenched in global finance—accounting for over 58% of global reserves and 88% of FX transactions as of 2024. For now, there is no clear alternative with the same liquidity, legal stability, and scale.

Potential Risks to Economic Stability

Should trust in the dollar materially weaken, the implications could be substantial:

- Higher interest rates: A decline in global demand for Treasuries would necessitate more competitive yields, increasing the cost of servicing debt and potentially crowding out domestic investment.

- Refinancing challenges: With nearly $34 trillion in national debt, the U.S. faces substantial rollover risk. A loss of confidence in U.S. fiscal sustainability could trigger market volatility or even a bond market correction.

- Imported inflation: A depreciating dollar would make imports more expensive, squeezing households and small businesses, especially in sectors dependent on foreign inputs.

- Geopolitical influence erosion: The U.S. dollar’s dominance gives Washington unique leverage through sanctions and capital controls. A decline in its use could reduce the effectiveness of these tools

America’s Triple Crisis (2025)

Now in 2025, the U.S. is dealing with three converging crises that stem from the choices and shifts of past decades.

The Manufacturing Crisis

- The decline: U.S. manufacturing now makes up just 11% of GDP, down from over 25% in the mid-20th century. Since 1997, America has lost 5 million manufacturing jobs.

- The cost: The hollowing out of industrial towns has driven economic stagnation, social decay, and political polarization. Entire communities have become dependent on service jobs or government aid.

- The pivot: COVID revealed the danger of relying on foreign producers for essentials. Now, reshoring efforts are gaining traction. But labor shortages, high domestic costs, and global competition pose serious challenges.

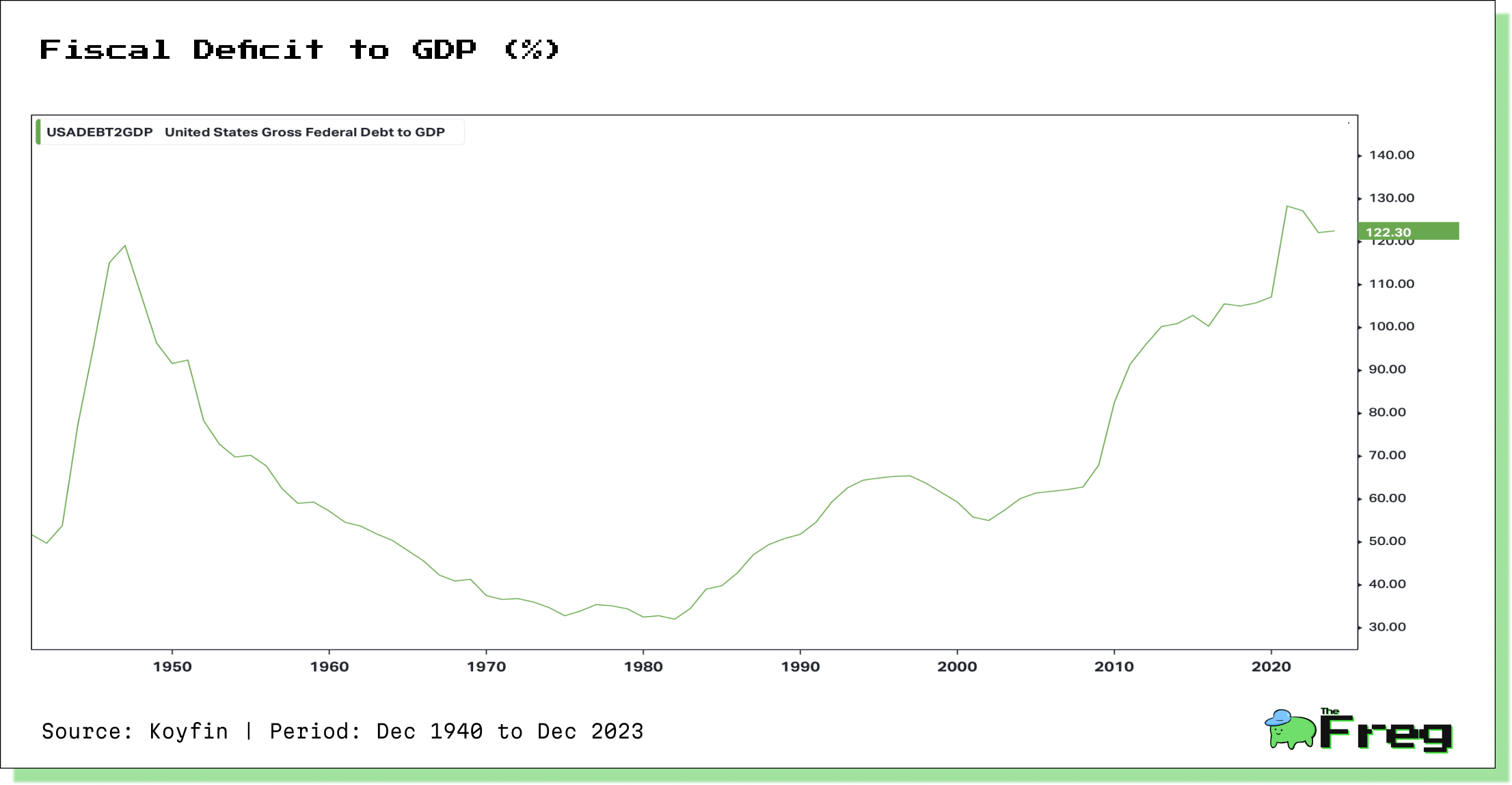

The Fiscal Deficit

- The ballooning burden: As of early 2025, the U.S. federal budget deficit reached $1.146 trillion in just five months. By year-end, it could hit $1.9 trillion.

- The drivers: Rising interest rates are making debt more expensive. Mandatory spending—on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid—keeps rising. The legacy of COVID stimulus and tax cuts adds pressure.

- The consequence: The U.S. has less room to invest in the future—in infrastructure, innovation, and education. And it becomes ever more dependent on foreign lenders to finance its debt.

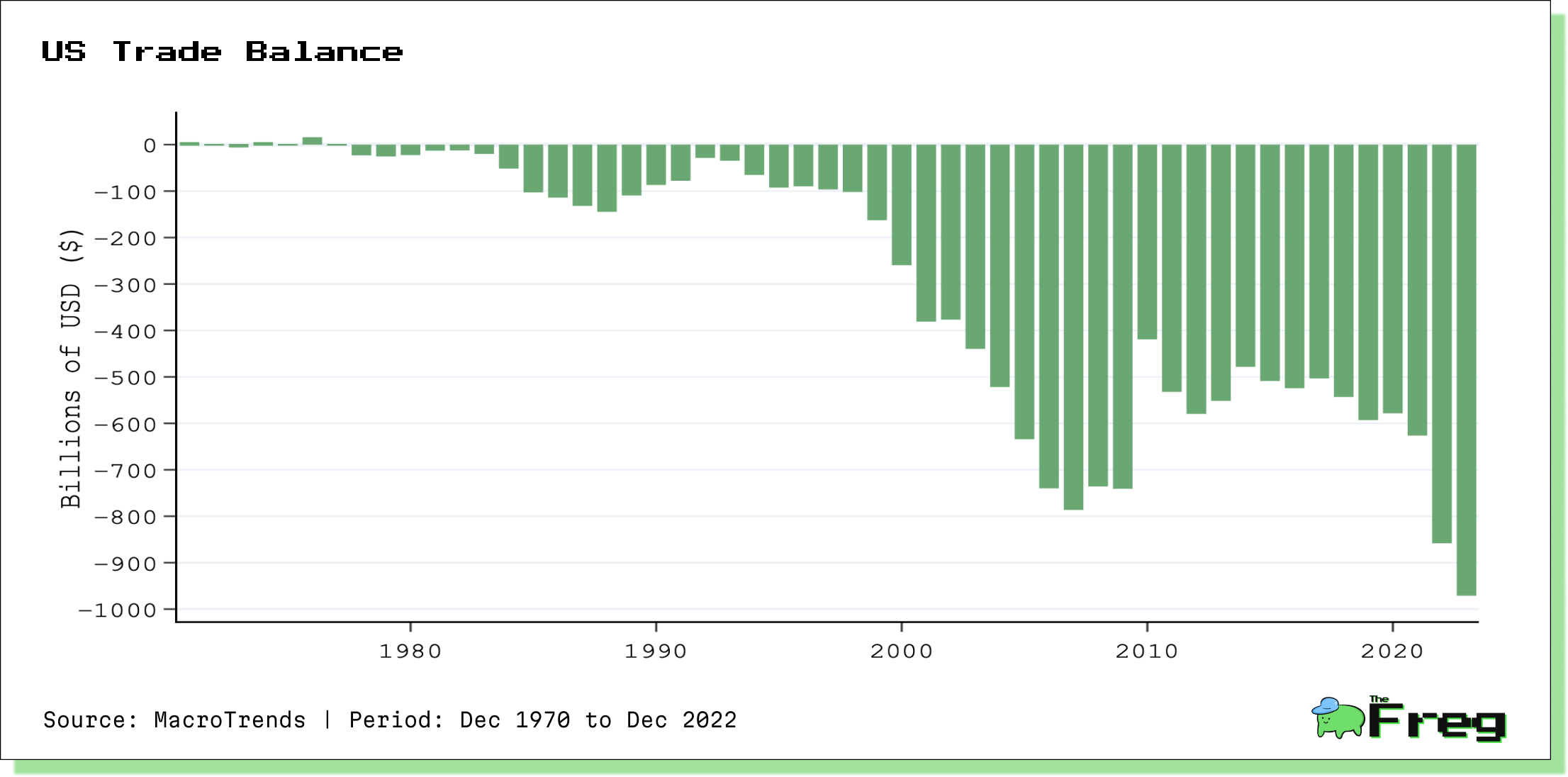

The Trade Deficit

- The imbalance: In 2024, the U.S. ran a record goods trade deficit of $1.2 trillion. Even agricultural trade—a long-time strength—turned negative.

- The causes: A low savings rate, globalized supply chains, and weak industrial competitiveness all contribute. New tariffs haven’t reversed the tide.

- The fallout: Persistent trade deficits require foreign countries to hold U.S. dollars or Treasuries. This props up the dollar—but also increases America’s external liabilities.

Intersections: A Vicious Cycle

These crises feed into each other:

- Manufacturing decline fuels trade deficits.

- Trade deficits worsen fiscal pressures by increasing debt servicing needs.

- Fiscal constraints limit the resources available to rebuild domestic industry.

It’s a negative feedback loop that’s hard to break without bold, coordinated action.

Trump’s Approach: High-Risk Recalibration

Amid America’s triple crisis—President Donald Trump has re-emerged with a high-stakes policy playbook. His approach hinges on three pillars: aggressive tariffs, expansive tax cuts, and reshoring-focused industrial policy. While designed to reverse decades of economic drift, the strategy has drawn significant scrutiny.

Trump has declared the decline of U.S. manufacturing a national emergency. To reverse it, he proposes a series of sweeping trade barriers and reshoring incentives:

- Tariffs: A universal 10% tariff on all imports, with higher rates on key trade partners—China (34%), the EU (20%), and Taiwan (46%).

- Reshoring Push: The idea is simple: make imports more expensive to compel companies to bring production back home.

- Infrastructure & Energy: Trump’s rhetoric emphasizes investment in energy and domestic factory construction as catalysts for revival.

Challenges:

- U.S. production costs remain significantly higher than those abroad.

- Labor shortages persist in key industrial sectors.

- A strong dollar continues to hamper the competitiveness of American exports.

The Costs and Consequences

- Inflation: Higher import prices contribute to persistent inflation, projected at 2.7–3.3% in 2025.

- Recession Risks: Goldman Sachs estimates a 35–60% chance of recession due to falling consumer spending and increased business costs.

- Job Displacement: Reshoring has yet to materialize at scale, and tariffs may trigger job losses in trade-exposed sectors.

- Trade Fragmentation: Retaliatory tariffs and supply chain shifts to nations like Vietnam and Mexico threaten global trade cohesion.

- Geopolitical Strains: Targeted nations may pivot toward China or Russia, accelerating de-dollarization and bypassing U.S. sanctions.

- Global Slowdown: The IMF forecasts sluggish global growth (2.3% in 2025), driven in part by U.S. protectionism.

Potential Upside:

If paired with long-term investments in infrastructure, education, and industrial policy, Trump’s protectionism could eventually revive American manufacturing. However, such transformation demands bipartisan continuity and time—two factors in short supply.

Trump’s economic agenda represents a bold attempt to confront systemic weaknesses. But without careful calibration, it could amplify the very problems it seeks to solve. Whether this high-risk recalibration can yield sustainable results—or simply stoke short-term political gains—remains a defining question for the U.S. economy.